Throwback Files: How YouTube autoplay gave a lost Japanese classic new life

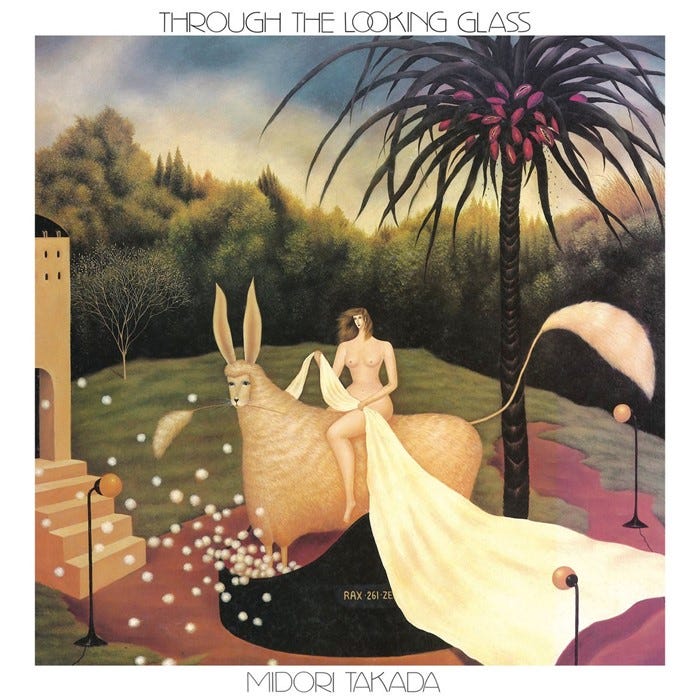

Midori Takada’s Through The Looking Glass almost vanished when released in 1983, but thanks to a quirk of the video streaming platform, it’s been hailed as an ambient masterpiece

Selected Works is a weekly (usually) newsletter by the Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa (Wellington, New Zealand) based freelance music journalist, broadcaster, copywriter and sometimes DJ Martyn Pepperell, aka Yours Truly. Most weeks, Selected Works consists of a recap of what I’ve been doing lately and some of what I’ve been listening to and reading, paired with film photographs I’ve taken + some bonuses. All of that said, sometimes it takes completely different forms.

Originally published through Dazed Digital on April 3rd 2017. Special thanks to Selim Bulut for giving me the opportunity to write this feature at the time. It was a huge confidence boost.

Throwback Files: How YouTube autoplay gave a lost Japanese classic new life

Midori Takada’s Through The Looking Glass almost vanished when released in 1983, but thanks to a quirk of the video streaming platform, it’s been hailed as an ambient masterpiece.

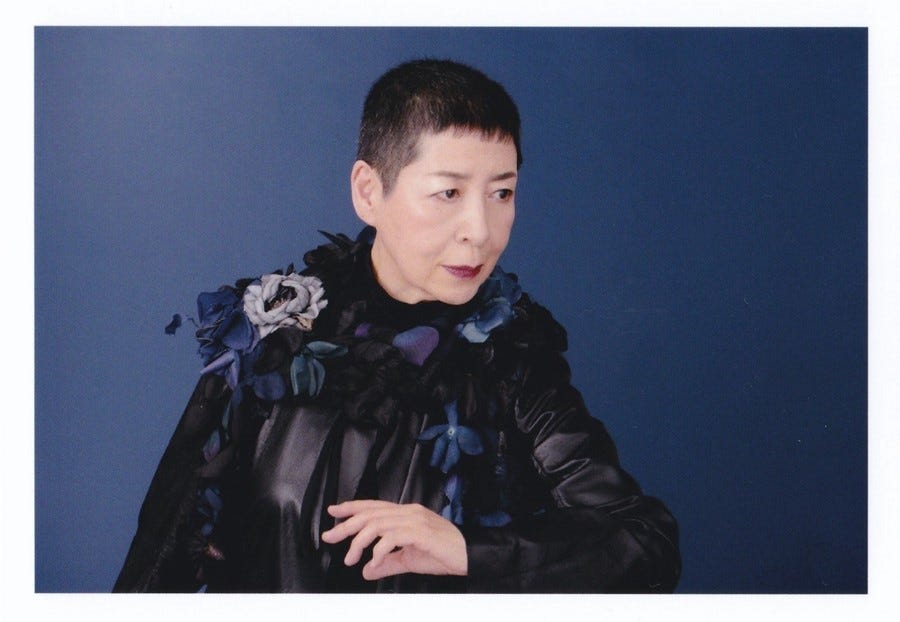

In an alternate timeline, Japanese composer and percussionist Midori Takada’s 1983 debut solo album Through The Looking Glass was greeted with rapturous praise. Critics who had already marvelled at Takada’s percussion group Mkwaju Ensemble marvelled again at the evocative, atmospheric textures and intertwined rhythmic structures depicted within her singular musical vision. Anointed as a logical successor to Terry Riley, John Cage, and Brian Eno, her work served as a corrective to the male-dominated hierarchy that defined the early development of minimalism and ambient music. Beyond this redress, her seamless integration of traditional African and Asian music into the forms disrupted the Western bias of these pivotal musical movements.

In reality, the album sank without a trace. However, in the years that followed, Through The Looking Glass began to find a small but ever-growing audience, and with time it came to be considered one of the rarest artefacts of early 1980s Japanese music. Copies sold online for up to $750. With every purchase, discovery and listen – be it crackly vinyl or dubbed tape – the myth and legend grew. Eventually in early 2013, musician and blogger Jackamo Brown uploaded the full album on his YouTube channel, where it benefited from a peculiar aspect of the video-sharing platform’s functionality. When left to idle, YouTube’s ‘play next’ algorithm automatically selects and plays a new video. Although the inner workings of the algorithm are a closely guarded secret, its internal processes began to prioritise Through The Looking Glass as a recommendation for YouTube users with an interest in minimalism and unconventional electronica. Much like proto-vaporwave groups Seaside Lovers and Software’s 1983 and 1987 albums Memories in Beach House and Digital Dance, the record accumulated a new following online – since Jackamo Brown uploaded it, Through The Looking Glass has clocked up over one and half a million views on YouTube, remarkable numbers for a forgotten record from the fringes of an already fringe scene.

Despite this pleasing anomaly, and the accolades long awarded to it by record collectors and deep experimental music heads, the story behind Through The Looking Glass – and, by association, Takada’s personal story – have remained largely obscured. But a new reissue series (starting with Through The Looking Glass by New York record label Palto Flats and Geneva’s WRWTFWW Records, with reissues of her Mkwaju Ensemble and Lunar Cruise group albums setto follow) is slowly giving Takada the wider recognition her work so richly deserves. “Only a few things tend to stay with you,” enthuses Palto Flats’ Jacob Gorchov. “This album had a presence that was completely unique, and I was drawn to it – it’s something I’ve always returned to.”

“Music is reality and unreality,” Takada states over email. ”Common sense and anti-common sense. Something that has meaning and no meaning. What was recorded once is now an illusion. An image of a mere moment in the past. Isn’t a mirror like an endeavour of layering an illusion upon an illusion?”

Born in Tokyo in 1951, Takada’s journey into illusion began in the 1970s, a decade where the post-WWII economic growth and restoration of the 1950s and 1960s gave way to a new focus on quality of life in Japan. As the Vietnam War ended, the Japanese youth of the era took their cues from American hippy culture. They strived for a freer society and an escape from the conservative values of the past. Takada was part of this generation. Like many, she was captivated by the playful pop psychedelia of The Beatles. From that starting point, she discovered progressive rock and free jazz, before journeying deeper into minimalism, ambient and early experimental while studying western classical music at the Tokyo National University of The Arts.

“In an alternate timeline, Japanese composer and percussionist Midori Takada’s 1983 debut solo album Through The Looking Glass was greeted with rapturous praise”

Takada played the piano from an early age, and took up percussion at 13. Given her background, pursuing a career as a professional musician made sense. In 1978, she made her debut as a percussionist in the Berlin RIAS Symphonie Orchestra at the Berlin Philharmonic. “Up until this point, my life was quite normal,” she recalls. ”Afterwards, I started to become fond of other styles of music apart from classical.”

In Berlin, Takada’s growing love of minimalism and increasing scepticism towards Western classical music led her towards the rich possibilities offered by free jazz and traditional African and Asian music. She also began to collaborate with other fine artists within the realms of dance and theatre, created a performance piece with female bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, and travelled to Bali to study Gamelan music. “Music does not evolve by itself,” she writes. “It is always under the influence of many things. So, as such, at the time I was also heading towards being active in other fields of arts as well.”

“Although Through The Looking Glass’ conceptual investigations of the physicality and colour of sound, time, and perspective only resonated with a few at the time, it wouldn’t be like that forever”

In those years, it was difficult to find information about African music in Japan. Takada would attempt to notate rhythms and melodies from field recordings, and then try to play them back. When Ghanaian master gyil (xylophone) player Kakraba Lobi and Senegalese griot Lamine Konte came to Japan, Takada collaborated with both of them. Thanks to Korean musician Chi Soung-ja, she discovered the feel and depth of traditional Korean music. “These experiences were quite valuable to me,” she says. “I don’t think there will ever be other musicians like them to emerge again. What I obtained from them was quite immense.” Inside the structure of traditional Korean rhythm, she discovered a yin and yang that was profoundly affecting. “When I realised this way of being, I was also made aware of the importance of achieving balance as a person,” she admits. As a result, I felt that I wanted to be equal to all of the sounds that exist in this world.’

With Mkwaju Ensemble, Takada began to integrate minimalism and traditional African drumming. In 1981, they released two remarkable records through the Better Days label, Mkwaju and Ki-Motion, before wrapping the project up due to economic difficulties. “We had members who got jobs outside of Tokyo, and it became difficult to remain active as a group,” Takada admits. “I remember thinking of ways to perform solo.”

Takada took her next step towards solo work early in 1983, when, at age 32, she spent two intensive days recording at Victor Aoyama Studio in Tokyo’s storied Shibuya ward. Working with a recording engineer and amongst other things a mixture of percussion instruments, chimes, recorders, reed organ and piano, she carved out the four-song suite that would become Through The Looking Glass. “A huge amount of concentration and energy was necessary,” she explains. “Each composition existed in my head, but the notation of it was next to impossible. Similar to painting, I layered each sound one by one. I did not lose my initial image, even until the very end of the recording. I think that the people around me at the time did not know at all initially what I was trying to create… I was astonished when I started to receive reissue offers from abroad.”

Although Through The Looking Glass’ conceptual investigations of the physicality and colour of sound, time, and perspective only resonated with a few at the time, it wouldn’t be like that forever. WRWTFWW Records co-founder Olivier Ducret first heard part of the album in the early 90s during a weekend listening session. “These are shady memories, nearly dreamlike, as that period was,” he recalls. “Listening to it was a unique and memorable moment.” In 2014, Ducret had the opportunity to meet Takada while touring through Japan. The following year, Palto Flats reissued underground Japanese post-punk and new wave icons Mariah’s final album Utakata No Hibi. Although it’s had a cult following in Japan since its release in the early 80s, and became a cratediggers’ favourite after influential Scottish DJ duo Optimo shared a song from it online in 2008, the Palto Flats reissue pushed it into the spotlight it deserved. Emboldened, Gorchov started reaching out to other Japanese artists on his wishlist. “I reached out to Ms. Takada, who was very kind in response,” he recalls. Soon afterwards, he had a conversation with Ducret. Given their mutual interest in her work, it made sense for the two labels to team up on a joint reissue. “I don’t normally use the internet… (so) I was astonished when I started getting reissue offers from abroad,” Takada admits. “The cutting of the vinyl (for this reissue) was done superbly, and the music and the artwork has been revitalised as well.”

“Everything we do leaves an impression on others, like ripples in water… That’s why it’s important to do this kind of work: to recognise the things that move us and to create more chances to positively influence others today and in the future. This is how we grow as individuals, as artists, and as a society.”

Gorchov discovered Through The Looking Glass while he was listening to a lot of minimalist music that was academic by nature. “I wouldn’t say soulless, but it wasn’t breathtaking in the same way,” he explains. Fed up with dry Western conceptual processes, when he heard Through The Looking Glass, it appealed on an immediate level. “One can’t really dismiss how organic the record is,” Gorchov continues. “She had such a clear focus and perspective going in, layering and building sounds with a deftness of touch, pinpoint focus, and warmth. It’s truly remarkable.”

Roger Bong, the owner of Honolulu-based Hawaiian music reissue label Aloha Got Soul and a huge ambient music fan, discovered Through The Looking Glass on YouTube while compiling a Hawaiian and New Age mixtape. He agrees with Gorchov’s assessment of the importance of its organic nature: “The music is at times almost primitive in the way that it draws the listener back to our beginnings on this planet Earth,” he enthuses. “It’s extremely grounding. It feels nourishing to listen to.” From his perspective, the beauty of Palto Flats and WRWTFWW Records reissuing Through The Looking Glass is in giving the music new opportunities to leap across generations and borders. “Everything we do leaves an impression on others, like ripples in water,” he continues. “That’s why it’s important to do this kind of work: to recognise the things that move us and to create more chances to positively influence others today and in the future. This is how we grow as individuals, as artists, and as a society.”

Following Through The Looking Glass, Takada continued to record, perform, and release music in solo and group settings with musician friends from across the African and Asian regions. 1990 saw her release the Lunar Cruise album with Masahiko Satoh, and in 1999, she released her second solo album Tree of Life. For the last 20 years, she’s composed and performed live music for theatre with Tadashi Suzuki and his Suzuki Company of Toga as part of their adaptations of Electra and King Lear. It’s a logical continuation of her early desire to explore the relationship between theatre, dance and music. “There, it was necessary for me to be not only a musician but also an actress who goes on stage,” she writes. “It was there where I discovered a vehicle where it is possible to create a musical space where ‘music, body, and space’ can unite, which was necessary for me to help elevate my artistry.” Takada loves the social nature of theatre and the power, possibility and potential of organised group work. “I found it to be a great opportunity to think about the primordial form of art.”

Four decades into her career, Takada frames her relationship with and role within music in simple, fittingly minimalist terms. “My assignment is to furnish the essence of the sound material in the best condition to the listener or space. While focusing on this endeavour, I transcend my sense of self,” she explains. “In my own way, I create sounds, and by myself, I emit them. It’s that simple. So to speak, it’s like living off the land.”

Through The Looking Glass is available for purchase through Palto Flats and WRWTFWW Records (here)

Postscript: It’s been close to six years since the reissue of Through The Looking Glass. In the wake of that release, Midori Takada had the opportunity to tour the world to appreciative audiences, record new material, and in essence, receive the flowers she has long deserved. All of that said, her story is not yet completely written. We’ll be seeing and hearing more from her in the years to come.