Obscure Desire

An interview with Andrew Waldegrave about 1980s club culture in Auckland, New Zealand.

Selected Works is a weekly (usually) newsletter by the Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa (Wellington, New Zealand) based freelance music journalist, broadcaster, copywriter and sometimes DJ Martyn Pepperell, aka Yours Truly. Most weeks, Selected Works consists of a recap of what I’ve been doing lately and some of what I’ve been listening to and reading, paired with film photographs I’ve taken + some bonuses. All of that said, sometimes it takes completely different forms.

When you talk about the storied tales of global dance music, club culture and nightclubbing in the late 1970s and early 1980s, one of the recurring themes is the importance of open-minded and open-eared spaces where dancers, DJs and performers found the freedom to be themselves. In New York, the club kids danced to the infectious selections of the late great DJ Larry Levan at the Paradise Garage. Over the Atlantic in Manchester, acid house, rave, and dance rock kept the dancefloor moving at The Haçienda. At the bottom of the globe in Auckland, the largest city in New Zealand, the place to be was A Certain Bar.

Located on the corner of Wellesley Street and Albert Street in the inner city, after opening in May 1982, A Certain Bar quickly became ground zero for the first wave of club culture in the city of sails. Inside, a diverse crowd of new romantics, punks, queer scenesters, breakdancers, freaks and weirdos would gather at night to hear the owners, Peter Urlich and Mark Phillips, and friends of theirs like Simon Grigg and Patrick Waller, aka DJ Dubhead, spin an equally eclectic range of upfront club music - post-punk, synth-pop, new wave, electro, technopop, RnB, pop, EBM, industrial, early hip-hop and other oddities of the era.

For Andrew Waldegrave, one of the trio of fashion scene misfits who later founded the cult New Zealand dance-pop trio Obscure Desire, partying at A Certain Bar was a revelation. “One of the big things about that era was the arrival of the 12” single remix,” Waldegrave remembered. “Those big production long remixes were a major thing for us. It was just fantastic.” After hearing what the English producer Trevor Horn was doing for the Sheffield pop group ABC, Waldergrave was all in.

At A Certain Bar, Waldegrave found himself caught in the new vibe. From his perspective, the angular guitar sounds of punk and post-punk represented the past. Instead, he was enraptured by synthesisers, drum machines and the physical power of DJ edits. The future was calling. “We were done with all that sort of guitar thing,” he said. “We wanted to do something completely different. You have to remember that things were changing at such an incredible rate in the eighties. Hairstyles were going from extremes, short to long in months, and music was doing the same thing!”

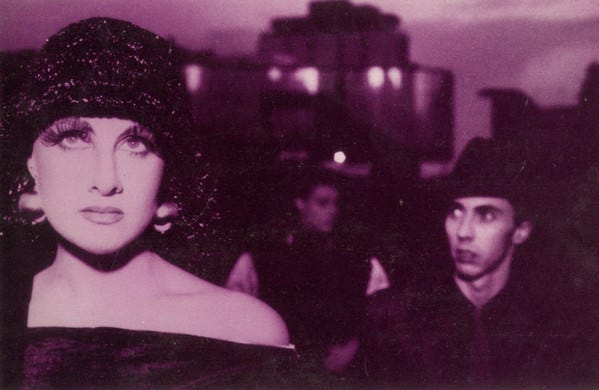

In 1986, Waldegrave and his future bandmates, Grant Mitchell and Giselle Trezevant, used the inspiration they first found at A Certain Bar to craft a small but perfectly formed collection of fashion-forward art-pop, boogie, proto-house and lounge songs that timestamps of an all-too-brief golden moment in Antipodean club culture. In the decades since that brilliant and blinding flash, Obscure Desire - singular within the histories of New Zealand music - gradually fell into actual obscurity before developing a global cult reputation over the last decade.

Since then, their signature self-titled 12” EP, originally released through the small Auckland-based independent label Pagan Records, has become a sought-after Discogs rarity and found its way into radio broadcasts and DJ mixes from China Social Club, Chuggy, Danza, Anu, and Flo Dill. Fittingly, “Obscure Desire” has just been reissued by Emotional Rescue and Utopia Originals, providing the perfect opportunity to investigate Waldergrave, Mitchell and Trezevant’s story.

After arriving in Auckland from The King Country in the Western North Island, Waldegrave dropped out of music school at the end of his first day. “Everyone there looked like Jesus,” he said. “They looked at me in horror; I looked at them in horror and left.” He worked briefly in retail before finding his groove as a hairdresser in the early eighties. “In those days, you had to choose a profession,” he laughed. “You either became a professional, plumber, hairdresser, or whatever.”

Having grown up playing the piano and the violin and listening to Neil Young, Jethro Tull, Wings and Abba in rural New Zealand, his musical perspective was slanted in unexpected directions. There can’t be many people who got into The Beatles through listening to “Wings at the Speed of Sound”, but for Waldegrave, that was just his reality. “I'm one of those people with a weird view of music,” he explained. “To me, there was The Beatles, and then there was Chic. Most people would say the music went from The Beatles to David Bowie, and this, that, and the other. But for me, it went from Beatles to Chic. I've believed that all the way through and all the music I've loved since then, there's a connection between those two things.”

Throughout the first half of the decade, he spent every spare evening or weekend moment out partying in Auckland nightclubs and discotheques like A Certain Bar, Quays, Zanzibar and The Six Month Club. This was the context within which Waldegrave befriended Mitchell and Trezevant. “In those days, you didn’t have to keep in touch with people,” he remembered. “You just went out to the discos on Friday night, and everyone was there. It was a party culture. That’s how I met them and became very friendly with them.”

In 1985, Waldegrave bought into an existing fashion boutique and salon on Albert Street in the inner city, Obscure Desire. Founded one year earlier by the model and fashion designer Megan Douglas (the daughter of the then New Zealand Finance Minister Roger Douglas) and the hair and makeup artist Carron Sheffield, Obscure Desire provided a full styling service for its customers. “It was a big, industrial-looking space,” Waldegrave recalled. “The front half was clothing, and the back half was hairdressing and makeup.” By the time he’d bought into the business, Trezevant and Mitchell were both working there.

Over casual conversations, Waldegrave and Mitchell discussed making music together. After realising they needed a vocalist, they asked Trezevant to join them. In light of the modernist fashion context in which they were located, they named their group after the business they all worked at, Obscure Desire. “We were trying to do a big production thing, like Trevor Horn’s ABC remixes,” Waldegrave laughed. “Naively, we had no idea of what was involved with that. So, in the end, we ended up with what we had.”

As the New Zealand music businessman and writer Simon Grigg observed about the trio in an article for Audio Culture called Ten Auckland inner-city club hits, 1983 to 1988, “They were club kids—faces in the then-current hippology—and they decided to make a record.” “Fashion was formulated by musicians in those days,” Waldegrave explained. “If you wanted to dress up and show you were the best, you had to do it yourself. You either get someone to make you the clothes, or you bought vintage.”

Obscure Desire went to the next level when Waldegrave purchased a Casio CZ1000, a Yamaha DX7, and a Roland TR-909 drum machine to get things started. “I had a lot of confidence in Grant,” he continued. “That's why I went ahead with this project; he was multi-talented and pushed through.” After familiarising themselves with their gear, Obscure Desire prepared to record their first demo at the then-newly opened 91 FM radio station on Symonds Street. “The engineer there was really good,” he remembered. “He made us do the track over and over again and drilled us into shape. From there, we went off to see who might want to release the record.”

However, reality set in somewhat after their first meeting with a major label A&R. “We got dressed up and walked in there looking fantastic,” Waldegrave said. “The guy quite liked our demo, but he looked at us and said, ‘What I’d like you to do is take six months off, go on the dole, smoke dope and write songs.’ I remember my mouth just about hitting the ground. I was like, I’m a business owner and look fantastic. What are you talking about? That was when I realised the culture shock of the difference between what was going on with us and the music scene.”

Despite that reality check, Obscure Desire found an ally in Trevor Reekie, one of the founders of Pagan Records. “Trevor was great,” Waldegrave said. “He was there to help you. He produced. He played on stuff. He organised the other musicians.” With Reekie’s assistance, Waldegrave, Mitchell and Trezevant pulled together a collection of songs, including ‘Bullet’, 4a’, ‘I Wonder’ and multiple versions of their self-titled single, two of which were remixed in London by the dance-pop producer Liam Henshall. “I love analog-sounding music, but I don’t know if people really realise how difficult it was making it,” Waldegrave noted. “Even when we did the title track on a 24-track desk, we had to use so many channels to get rid of hiss and tape noise.”

Thinking back to those challenging sessions, Waldegrave remembered a few anecdotes about some of the songs. ”The reason we ended up with ‘Bullet’ was because Grant had this great idea doing half of George Benson's 'On Broadway' and mixing in a chorus melody from The Wizard of Oz,” he explained. “‘I Wonder’ is some chords I had,” he continued. “Giselle wrote the chorus. Grant helped a bit with finishing it, but it was basically Giselle and me making a song about starting a new relationship. ‘4a’ was something Grant and Giselle did. ‘4a’ was short for Gabriel Fauré, a famous French composer. It’s inspired by his piece ‘Après un rêve’ (After A Dream). I think an unknown poet wrote the lyrics.”

At the time, Obscure Desire was vibing on a mixture of British dance music and American soul, RnB and disco/boogie artists such as Luther Vandross, Gwen Guthrie, Chaka Khan, and Sylvester. “We wanted to do something international, like what we were listening to at the discos every weekend,” Waldegrave continued. “It was as simple as that.”

In 1986, Pagan Records released three self-titled vinyl records from Obscure Desire, a 12” EP that combined four mixes of the title track with ‘Bullet’, ‘4a’ and ‘I Wonder’, and two 7” singles. Although their music slipped between the cracks with local radio, Obscure Desire’s self-titled debut single became an underground club hit in some of Auckland’s more progressive nightclubs. Driven by piano, slap bass, synths, boogie guitar licks and a dance tempo groove that wouldn’t quit, it set the scene perfectly for Trezevant’s simultaneously languid and soaring vocals of lust and desire.

Obscure Desire made their first and only live performance at The Six Month Club to celebrate the release. “It was a fantastic thing,” Waldegrave enthused. “We went over the top with how we looked and everything.” As part of the event, Megan Douglas organised a fashion show with an unusual array of models. It was a cultural confluence of all the different forces that animated Obscure Desire as a business, band and cultural worldview. “That was what it was all about,” Waldegrave said. “That was why we made the record. We just wanted to bring everything together. I worked on a lot of fashion shows and did film work. Megan was styling for bands. Everyone was into mixing things. It was just normal.”

Not long after, Waldegrave, Trezevant, and Mitchell took off for London to see what the larger world might offer them. However, rather than taking things to the next level, they hurtled headfirst into a meltdown-level disintegration as a group. While they were overseas, some of Obscure Desire’s music featured in the soundtrack to Gloss, a New Zealand television drama series about the lives of the rich, famous and fashionable people involved with a fashion magazine owned by the fictional Redfern family, before slowly fading from view until it’s recent renaissance.

“Living in the world and time we were, making this music just seemed normal,” Waldegrave said. “Why wouldn’t you do it? We didn’t really think about it all too much. If any sense had prevailed, we wouldn’t have done it because it was a hard slog to do. We were in our mid-twenties, and this was just our way of being involved. We weren’t thinking deeply. We were just thinking, do it, do it. We just had the drive to do it.”

Obscure Desire is out now in digital and 12" vinyl formats through Emotional Rescue and Utopia Originals. You can order a copy here.

FIN.