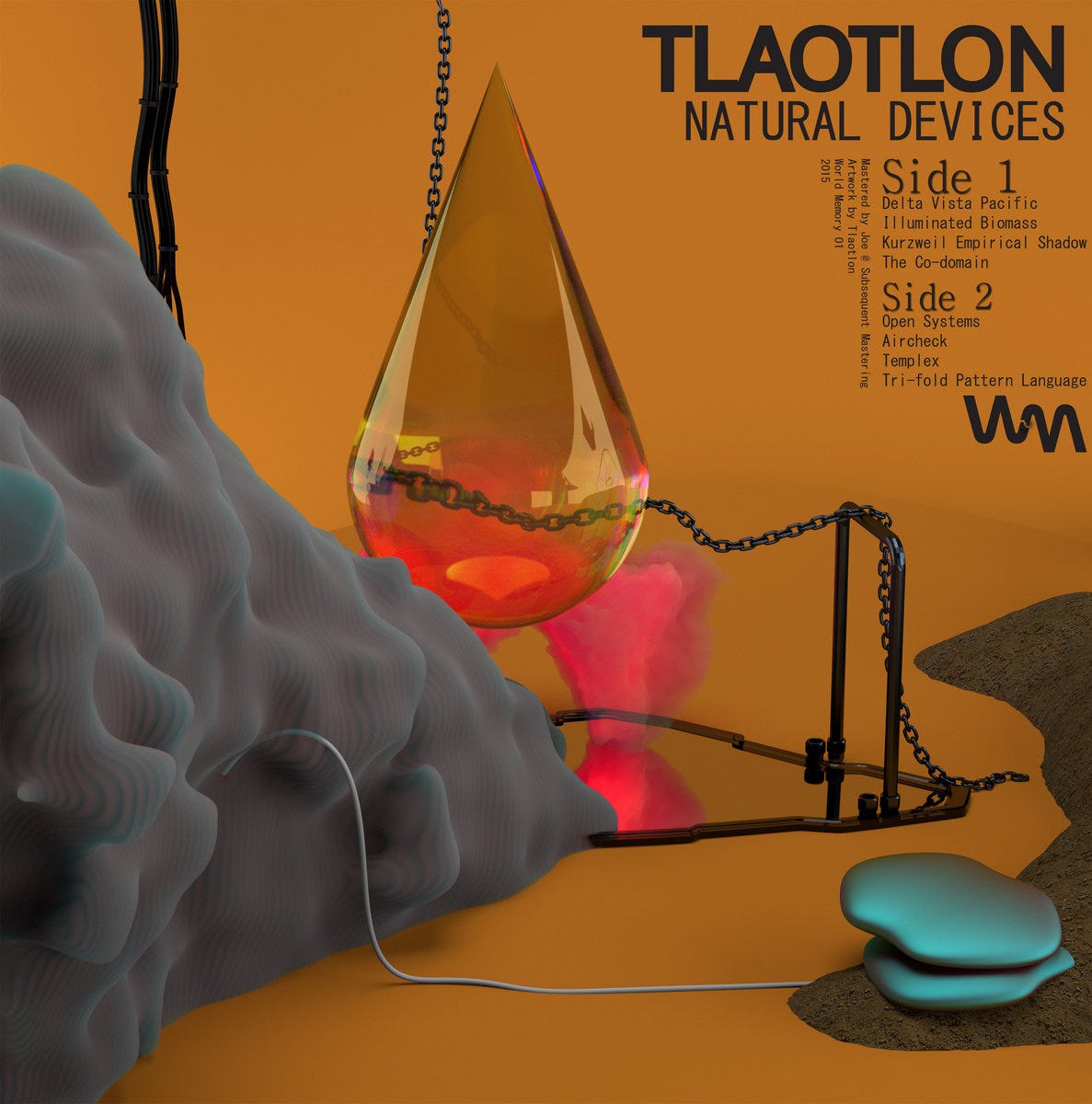

Midweek reissue: Tlaotlon

An interview I conducted with Jeremy Coubrough aka Tlaotlon for The 405 in February 2015

Selected Works is a weekly (usually) newsletter by the Te Whanganui-a-Tara, Aotearoa (Wellington, New Zealand) based freelance music journalist, broadcaster, copywriter and sometimes DJ Martyn Pepperell, aka Yours Truly. Most weeks, Selected Works consists of a recap of what I’ve been doing lately and some of what I’ve been listening to and reading, paired with film photographs I’ve taken + some bonuses. All of that said, sometimes it takes completely different forms.

In 2015, I interviewed the then-Melbourne-based New Zealand multi-instrumentalist and electronic music producer Jeremy Coubrough about his remarkable abstract techno project, Tlaotlon, for a now-defunct culture website in the UK called The 405. Nine years later, Jeremy lives in Berlin, where he continues exploring his avant-garde musical impulses.

Along the way, he moved into equally abstract visual art and 3D printing-based creative practices. I should really have an updated chat with him about all of this stuff, but today, before I head to the airport, let’s revisit my nearly decade-old interview with him. There’s some good stuff in here.

"When I was thinking about making Natural Devices, I was thinking about when people say my music is challenging or that they don't get an emotional resonance from it," reflected Melbourne-based New Zealand musician and producer Jeremy Coubrough. "That's not really what I wanted them to get or hear. I wasn't pissed off about it, but it did make me think that it would be good for me to clarify what the project was about, both for myself and the listener."

Better known in fringe music circles as Tlaotlon, Jeremy was chain-smoking outside a cafe in Wellington (the capital city of New Zealand) while recovering from performing at a loft rave the night before. Between drags and sips of strong coffee, he offered up thoughts on his psychedelia and cyberpunk-informed techno music and its place within "the world of virtual life technology and handheld media devices."

His fourth album in three years, Natural Devices, saw Jeremy refining and polishing the syncopated man/machine rhythms and virtual reality soundworlds of his past singles, EPs and records. As part of this development, he decided to use more conventional musical language in his composition process, or as his album title suggests, natural devices.

"What makes people engage more with a song?" Jeremy mused. "It's the techniques of songwriting and composition. They're devices. As a composer, you want the listener to feel this or hear that, and the way you signify that in popular music is with a breakdown, bridge or a rise and a drop. To me, this isn't really talked about in music, but you're manipulating someone's emotional response. With music people can get caught up in this idea that the performer is intuitive and magic, but they're not. Even people who write intuitively are at the same time making a very conscious decision to use this technique or device to drum up a particular reaction."

Having studied music when he was younger and played in live bands since his teens, Jeremy was very aware of the above set of processes. While he wanted to employ them, he needed to find a way that made sense within Tlaotlon. "I thought, if I'm going to use melodic material, what interests me?" he said. "I couldn't help but think about notification sounds, alerts, alarms and all these other attention-grabbing noises that permeate modern life."

Rationalising that these sonic artefacts could serve the same function as a pop hook, Jeremy set about finding ways to put them to work, in the process creating a secondary technological read on the album title. "It's about getting your attention and then fulfilling your expectation of what that alert is meant to be for," he elaborated. "It made perfect sense as a way to draw the world and the broader environment of now into the music."

Throughout the eight songs on Natural Devices, Jeremy shaped these devices into hypnotic melodies and textures, letting loose-limbed percussion patterns circle in and out of each other around a heartbeat bass drum pulse that falls on every beat. As a listening experience, it's captivating and special. For the creator, however, it was a crowning achievement within his initial goals when he established his Tlaotlon project in the late 2000s.

At the time, Jeremy was busy playing in bands like Orchestra of Spheres and Bright Colours. Although he was a prolific electronic music producer and DJ back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, he’d been wary of electronic music production for several years due to, as he put it, "...the data entry feeling of doing electronic music on a computer."

When regional dance sounds like kudoro and footwork started to make their way out of Angola and Chicago respectively, he was captivated, but not as captivated as he wanted to be. "I was hearing some really interesting dance music again," Jeremy said. "This stuff was getting closer to what I wanted to hear in dance music, but I still had problems and issues with it. I thought I'd put a critical lens on it and make some stuff again to try and address these issues for myself."

His biggest issue was with the metronomic rhythmic-grid club music continued to operate within. Having discovered techno in his teens, he understood this frame within the history of dance music, but he also felt something needed to change. "The rhythms of techno made perfect sense at the time they were first made," he reflected.

"Detroit had the automotive industry, and the idea of the factory assembly line seemed to influence the music of the working class. In Berlin, you cross that with the spectre of fascism and their military history, the sound of enforced order and stomping boots. Then, when you add the burgeoning utopian vision of the internet and the potential power of code and anonymity, 4/4 slamming 808 and 909 beats makes perfect sense,” he explained.

Twenty-plus years later, however, the cultural landscape has changed, and he wanted to do something different. “I wanted to use super digital equipment, but I wanted my structures and forms to be analogue,” Jeremy said. “I wanted them to have more in common with the way forces work in real or virtual environments: gusts of wind, waves of data, swarms of pop-ups or insects, replicating viruses, globs of accumulated data - that was what made sense to me.”

Although Jeremy wanted to invert the traditional rhythmic and functional mode of techno, he was careful to note he wasn’t saying this was how all techno should sound from that point. “I just want to know my contribution and what it could be,” he said. Across the album, he realises this digital naturalism, in the process opening new doors for those willing to follow or, better yet, find doorways of their own.

Released in 2015 via his own World Memory Records, Natural Devices arrived in an era of increasing fragmentation and widescreen openness within club music. It was a fitting time for Jeremy to be doing what he did. "I feel like you can put anything on the table, and people will be receptive to it," he enthused. "There is almost no centrifugal force anymore; everything is just happening in all these directions. Once you find your way into what is going on, there is so much great stuff to listen to right now. A lot of my favourite music of the last decade has come out over the last two years. That feels really significant to me."

FIN.