A step above chic

An interview with Panaché’s Freddie Thompson

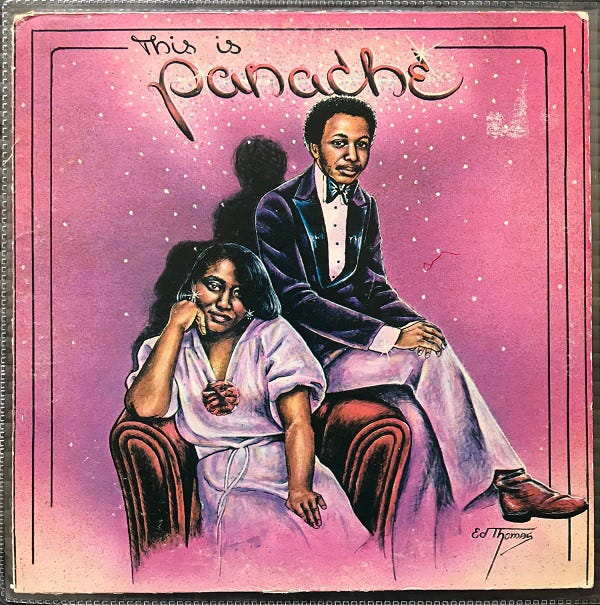

This is Panaché (1979) LP cover - Artwork by Ed Thomas

Originally released as a 12” single in 1982, ‘Every Brother Ain’t A Brother’ was the final record from Brooklyn multi-instrumentalist and producer Freddie Thompson’s Panaché band. Built around a fully-cleared bassline sample from ‘The Message’ by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, ‘Every Brother Ain’t A Brother’ plays out like a summertime stroll through New York in the early 80s. The streets are full of excitement, but as the lyrics, written by vocalist Denise Williams (not to be confused with Deniece Williams of ‘Let’s Hear It For The Boy’ fame) make it clear, they’re dangerous as well.

On the 21st of May Isle of Jura is releasing the first official 12” reissue of ‘Every Brother Ain’t A Brother’. A cult classic from the disco-rap era, the reissue includes the original vocal and instrumental versions of ‘Every Brother Ain’t A Brother’ plus a Jura Soundsystem special re-edit version with additional live percussion.

Earlier this year, I called Freddie at home in New York on his landline. We talked about his background before Panaché and the singles and album the group released. We also discussed the challenges they faced at the time and how things changed for them as the eighties unfolded. Easy going and generous in conversion, Freddie had some very sweet and sad stories to share.

Martyn Pepperell: You told me that you got your start playing music as a teenager in Brooklyn, New York during the late ‘60s. Can you talk about the role music played in daily life when you were growing up?

Freddie Thompson: Maybe every fifth young person wanted to get into music, and that's what we talked about. When we were walking the streets, you would always come by a couple of houses on every block where you will hear somebody practising some instruments, you will either hear a drummer down in the basement banging away, somebody blowing on a horn, or a guitar player playing through this amplifier. It was just a normal thing to do. Just like sports. Everyone wanted to be into music.

What sort of music did you gravitate towards at the time?

Motown and James Brown, James Brown was our guy. Yeah, there was a guy that inspired us to put our little band together, he had a James Brown copy band. He wasn't a great singer, but he was a great dancer. So he would do the performances around the community. Our school had a nice sized auditorium. So, we had these little after school program talent shows and all kinds of activities. He and his crew performed there from time to time. That inspired a lot of people who wanted to do something.

How did you get your start playing?

I was in a public school in Brooklyn, New York. They had a very elaborate music program there. They would hold concerts at the school, with their musicians and they had choirs, and they would perform. I mean, they’d do city competitions and things. This was a very elaborate music program. I started playing classical trumpet and guitar there. They had a music program after school where they were teaching us how to play folk music. I was toying around with that with my school band, and my other guitar player was telling me, “Fred, we can use these kinds of chords.” He showed me how to formulate chords that were being used by rhythm & blues music, you know, James Brown.

What were you doing musically before you formed Panaché?

We were working with a lot of different groups that came out of the community in Brooklyn. Like I mentioned to you before, music was like sports. Right in our immediate community, we had a group that came out that was called Crown Heights Affair. Now, I used to play the trumpet with an original member of Crown Heights affair, before they became before they changed the name to Crown Heights affair. Yeah, they were the band I mentioned to you that had the guy doing the James Brown copy. They were the original Crown Heights Affair.

Along with them, we had the group Brass Construction and moving along, we had the group Cameo. They were up the block from us. Larry Blackman and all of those guys, we all used to hang out together. Some of us used to loan each other our equipment because in those early days, all of us were poor and our parents didn't have a lot of money. So one guy would have an amplifier and another guy would have some drum pots. We would all borrow from each other. Someone would have a Shure P.A. column. We would trade and share each other's equipment when we had a show to do to help each other out. That's how we got by.

Were you playing music full-time in the ‘70s?

Oh no, it was just still on the side on the weekend and practising during the week whenever we could. We never totally went full-time, but we were working towards that.

Where did you get the band name Panaché from?

Well, after we have been working under different names for a while, I came across this guy, Carl Nelson. He was into DJing and was very active in the nightlife. Carl took a liking to what we were doing and wanted to work with us. He was the one that suggested that we take on that particular name. He explained it to us as a French word for style and elegance. At that time, Chic was just starting to get popular. Carl felt the word panaché was a step above chic.

Can you tell me a bit about the other musicians you were playing with?

Yes, the keyboard player, who was one of our main writers, was Douglas Glover. He was a self-taught player, and he was excellent. I don't know how he was able to excel to the level that he was without any musical training. I was musically trained, so I was always talking in musical terms. He would just sit down and play, and he was excellent with his playing, phrases, and songwriting.

The original bass player was Jonathan Lloyd, who went on to establish his own production company, New Systems Productions. We still play together, but he's done a lot of things with his operation. Then we had different personnel playing other instrumentation. I was a guitar player at that time. Then you had my wife at the time, Debra, who took over playing the bass and sang.

By the late ‘70s, music was changing. You guys were playing and recording a mixture of jazz fusion, funk, disco and rap. How did the landscape look to you at the time?

We kept changing with the times. Our first proper recording, that we made in a real studio, was a song called ‘Sweet Music’. We ended up recording four different versions of that song because the music kept changing and it was a great song. We always got a great response when we performed it, but it never quite took off, so we kept coming up with new ideas for re-doing it. We were trying to get signed by CBS at the time because we had a friend who worked with the A&R people there. But then that didn’t happen, because CBS locked the doors and stopped signing new talent, so we shopped it around to several different companies.

After that, this electronic instrument called the Pollard Syndrum came out. That was when we did the second version of ‘Sweet Music’ with the electronic drum that sounded like a whistle, and other synthesiser effects in it. Matter of fact, I bought the syndrum a day or two before the studio session. I was just really as experimenting as we were recording. That was the second version of ‘Sweet Music’ that we did with Panaché. It made a lot of noise in the clubs. We were promoting it through record pools, and we got a good response.

Then we had ‘Sweet Jazz Music’, like you were saying, the music was changing, so we hired an extra keyboard player. At the time, Bill Kamarra, who had Rota Enterprises, LTD and Nilkam Enterprises was our co-producer; but really he was our producer. He had a keyboard player he was using for a lot of his straight disco things. I thought maybe I could use him to give a little different flavour to the song than what we had already. We had him doing some things with the synthesisers on ‘Sweet Music’ but we didn’t really like it, so we had him do an acoustic track. I decided to use the acoustic track as an instrumental and call it ‘Sweet Jazz Music’. A year later, I met this guy who was fantastic on the synthesiser, so we re-recorded it again and came up with a final version called ‘Get Down To Sweet Music’.

How did you feel when drum machines and synthesisers started becoming commonplace?

It was rough for us because we were still musicians that were playing all live. You know, we were still used to going into the studio with live musicians. So when the synthesizer started taking over, you know, I had to put the horn down and put the guitar down. We started using the electronics and tried to adapt.

There was a radio jock at a former number one radio station here in New York called WWRL. He took a liking to us and started promoting the group. They were talking about taking us over to Europe because they had a lot of connections in England. That was when we started to want to go in different musical directions. My keyboard player, Douglas, who wrote a lot of songs and the original bass player, Jonathan, teamed up and started doing different production work together. I teamed up with my wife and some other people and continued with Panaché.

This leads us to Panaché's debut album, This Is Panaché?

Yes. That was something I was ashamed of because, at the time, we were rushed. We did a remake of ‘Not On The Outside’ by The Moments, Ray, Goodman & Brown, and we were getting a lot of airplay off it. Over in Europe, it made it onto a lot of radio playlists. Thing is, we didn’t have much of a budget either, and I wanted to capture some benefits from what was happening. We’d been hustling and investing without much of a return, so instead of putting out a single, I wanted to put out an album. We could make more money off selling an album, and that way, we’d have a budget to continue with.

With a few of the songs on the album, I took everything I had recorded before, went back into the studio and did a few different little mixes in order to come up with additional songs, like that one on there where I do ‘Not On The Outside’ as an instrumental. I hadn’t played the horn in over a year, and yet I was trying to play the horn in the studio to get a different version so I have enough songs for an album. It was a learning experience for me because I was doing all of the business, but with very limited knowledge of the business.

You released it yourself, right?

Yes. I owned my own label, Roché Records. I’d teamed up with a music business organisation, SIRMA. The Small Independent Record Manufacturers Association. It was very, very hard for the independent manufacturers to get airplay and distribution, so we all came together. We had about one hundred different independent record executives, and we were trying to work together with the majors because they were tightening the industry at the time.

Things were starting to happen and I wanted to capitalise on the airplay we were getting, but I didn't have time to do a professional album. I was very ashamed of the back cover of the album because we just threw that together. The front cover was done by an artist I hired when I was out doing on the road doing some promotion. He had done a lot of work for some major artists like Patti LaBelle, Chaka Khan, and some other big groups back in those days. He showed me his work, and it was just so fantastic. I had to hire him.

What was the story behind ‘Every Brother Ain’t A Brother’?

My wife at that time, Debra Thompson, was the female lead vocalist, along with two other vocalists that we had in a group that made up the frontline for Panaché. Our family was growing, and I think she was about six or seven months pregnant. We were getting all of this attention, radio stations, interviews and things. So she just didn't feel comfortable travelling around with a big belly and things. That's when we got Denise Williams to step upfront instead of being a background singer. She was the one that wrote that song, ‘Every Brother Ain't A Brother’. We were planning on doing a lot more, but we only got to do that one song with her.

For that one, we started utilizing some of the music that was on 'The Message’ by Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five. We just gave it some acoustic sound instead of a straight electronic sound. 'The Message' was all synthesizers, everything electronics, whereas we had all live musicians, but once again, on a limited budget. There were a lot of imperfections and things we had to just run with because we're looking at the clock and we’ve got like another four to five minutes to do a mixdown. We didn’t have any more money to buy any more hours, so we were always rushing through sessions.

What was the appeal of sampling music from ‘The Message’?

We purposely copied the concept of that song. I knew Sylvia Robinson and Joe Robinson from Sugar Hill Records through SIRMA, so after we’d done that, we sat down with them to discuss publishing shares, because it was our lyrics and arrangement, but their concept. They were a little puzzled at first because they figured we would wait until they had finished marketing what they had, but we thought it best to jump on their coattails. We really wanted to run with it, and they allowed us to do that.

What do you think Denise was thinking about when she wrote the lyrics to the song?

Well, at that time, we were talking about racial unrest. There has always been a lot of racial unrest in the inner cities in the states, not just in New York, but there was a lot of tension on the streets at the time. In our area, there was a lot of crime within the neighbourhood. You know, you had people who you grew up with - who committed crimes - coming through your window when you're not at home. So that's what motivated Denise to write that particular song.

She was good with writing poetry. We had planned to do a great deal more because she showed me a book that had about 30 or 40 poems that she wrote in it. When she showed me the one that was titled ‘Every Brother Ain't A Brother’, I told her, I think I can do something with this one. I had the help of the other two vocalists, who were pretty good with ideas and arranging and things. The four of us all got together and put that vocal arrangement on top of the music. That’s how that came about.

Where were you performing in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s? How often were you playing?

Mostly the East Coast. We got out of New York, but we didn’t get too far. You know, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, the tri-state area. We didn’t have management, but people liked what we were doing and would team up with us. We were driving up and down the East Coast, going to radio stations, trying to sweet-talk the program directors and paying local promoters to represent you at radio stations, we did a lot of that. That's why the studio budgets were so small because there was so much money going elsewhere.

Did you play your own shows or open for other acts?

Both. We were able to tie in with a lot of artists who had major major deals and were doing shows around the area. Since I was out there hustling and doing things, I was always able to make contacts. I would explain to them that our group would work as an opening act as a promo. They could put us on the bill, we’d do a performance, and they wouldn’t have to pay us.

We opened for Roberta Flack, and we played with some of the nostalgia groups like The Drifters and The Marvelettes. Somebody’s friend would always give us a spot, and aside from that, we were doing our own shows in local clubs and dancehalls. Philippé Wynne from The Spinners wanted to do some things with us. He was being managed by Sugar Hill and he followed us into the carpark when we were leaving to discuss doing some things. We were fortunate to be able to tie in with a lot of successful people, but we just couldn't get our group off the ground.

When did things wrap up for Panache?

Well, we never really broke up. We just started doing different things. Like I said, my keyboard player and my bass player, they started producing independently because they wanted to go a different route. But the three of us were still working together. I would come in and lay down horn lines for them, or play guitar and stuff. Even today, we still work together, but it was more behind the scenes for other people.

I started working with some of the nostalgia acts and got real busy with that. I brought in some of the Panaché musicians like my keyboard player, Douglas Glover, and we worked together for another twenty years backing acts. I also brought my bass player in on a few shows, even my wife Debra. She was there with us most of the time playing bass.

Panache was always there, we just became the backup band for that group or the studio group for this artist. We stopped trying to become stars because we were so busy working in the industry. It’s funny, we had a lot more success that way then when we were trying to make it as recording artists.

The Isle of Jura 12” reissue of ‘Every Brother Ain’t A Brother’ is available for pre-order (here)

WHAT I’VE BEEN DOING:

In the weekend, Palestine’s Radio Alhaha broadcast my latest guest DJ mix, ‘It’s Over.’ If you want to check it out, the archive copy is up on my Mixcloud. Expect 60-minutes of of recent releases and reissues from This Person, Howie Lee, Height-Dismay, Nubuck, Scribble, YL Hooi, Joanna Law, Sjunne Fergers Exit, Ichiko Hashimoto, The Frenzied Bricks, Irena and Vojtěch Havlovi, and Cy Timmons. (Stream here)

Dublab has uploaded the archive stream of the 90s/early 2000s NZ hip-hop mixshow I recorded for them recently. ‘Summer In The Winter’ is a 60-minute celebration of the era when a generation of local rappers, DJs, producers and musicians found a sound that rang out through the South Pacific. You can stream it (here).

I wrote about ten excellent albums and EPs that were released over the last three months for Dazed Digital. My recap features YL Hooi’s hazy, late-night soundscapes, Meemo Comma’s anime-inspired compositions, and an eight-year anniversary compilation courtesy of Seoul-based nightclub Cakeshop. Check it out (here).

Finally, I reviewed Strangelove Music’s remarkable new artist compilation, Childrens Mind, for Test Pressing. Childrens Mind collects up seven songs from deceased Swedish multi-instrumentalist and producer Sjunne Ferger, and his group Exit. The opening track ‘Awakening’ is unreal. Read more (here).

WHAT I’VE GOT COMING UP:

On Sunday afternoon, I’m one of the change-over DJs on the Radio Active 88.6 FM stage at Newtown Festival in Wellington. If you’re in town, I might see you there.

THAT’S ALL FOLKS!!!